TAPU

How to Draw Birds

Jakob Engel

Impressum

Betreuer: Jeanne Faust / Wigger Bierma / Ralf Bacher / Hannah Rath / Claire Gauthier

5/2017

Auflage: 70

Stk.

Material 379

Materialverlag – HFBK, 2017

Drucktechnik

Hardcover mit Texteinleger

80 Seiten,

Vierfarb-Digitaldruck; HP-Indigo,

Hardcover in Leinen eingeschlagen, Fadenbindung

39,— Euro

Beschreibung

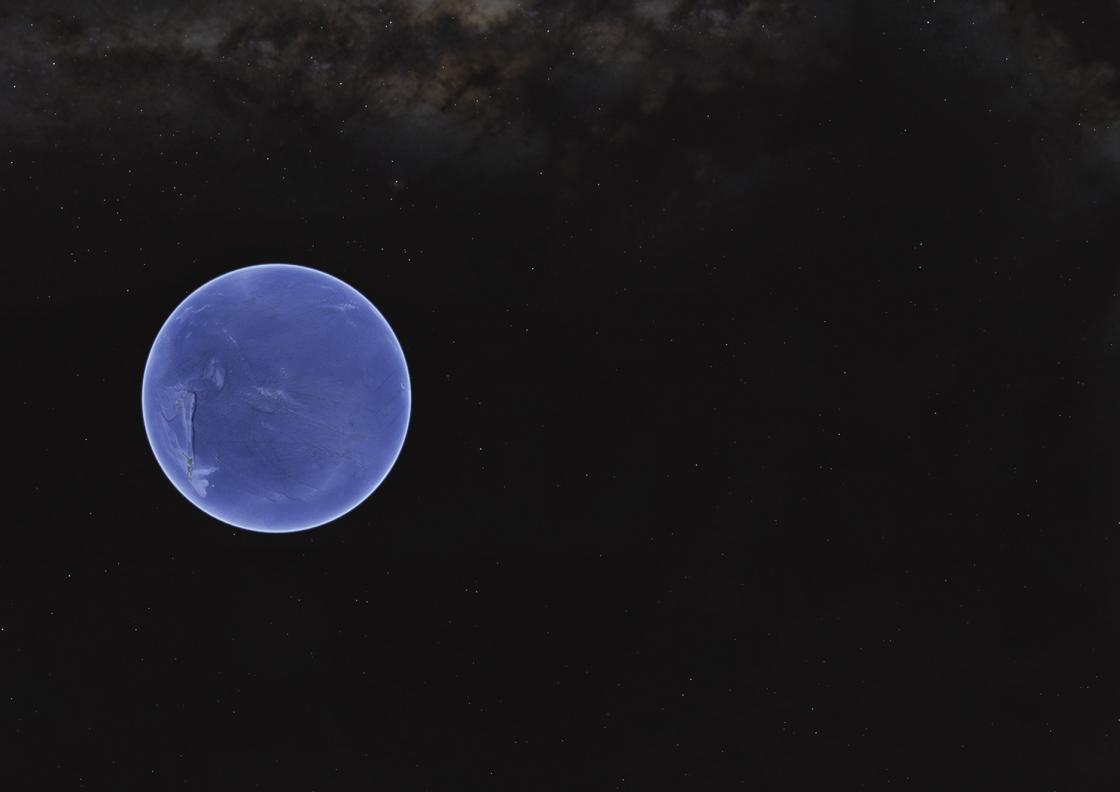

1773 – mit achtzehn Jahren – zeichnete Georg Forster seinen ersten Vogel. Mit seinem Vater, dem Biologen Georg Reinhold Forster, begleitete er Kapitän James Cook auf einer Expedition im Südpazifik. Cook hatte den Auftrag, mit seinen Schiffen Resolution und Adventure die hypothetische Terra Australis zu entdecken – ein großer Südkontinent, der die nördliche Landmasse ausgleichen müsste. Dies war seit der Antike die vorherrschende Meinung in Europa. Cook fand jedoch nur kleine Inseln. Wieder in Europa angekommen schrieb Georg Forster anhand seiner Aufzeichnungen einen Reisebericht, der schnell populär wurde und die Vorstellung der Europäer von der fremden Südsee und dessen Einwohnern prägte.

Mit seinem Text brachte er auch den Begriff tapu mit nach Europa. Tapu – „das Gebot zu meiden“, wie er es definierte, ist im pazifischen Raum ein weit verbreitetes komplexes kulturelles Konzept. Es leitet sich von den zwei Wörtern ta pu ab, die auf der Insel Tahiti die Bedeutung von etwas „ganz Gekennzeichnetem“ besaßen. Als ursprünglich eher positiv konnotierter Begriff wurde er im europäischen Sprachgebrauch ins Negative umgedeutet – repräsentierte er doch das mythische Berührungsverbot, welches die Aufklärung damals gerade zu bekämpfen versuchte. Doch wie Adorno und Horkheimer in ihrer “Dialektik der Aufklärung” anmerken ist “die reine Immanenz des Positivismus [...] nichts anderes als ein gleichsam universales Tabu. Es darf überhaupt nichts mehr draußen sein, weil die bloße Vorstellung des Draußen die eigentliche Quelle der Angst ist.“

Den Blick bis zur nächsten Bushaltestelle riskiert Jakob Engel und konfrontiert Forsters Erzählung der frühen Kolonialgeschichte im Südpazifik mit seiner Bilderfolge. Er dramatisiert Teile von Forsters Text zu einer Art Theaterskript und kennzeichnet seinen Reisebericht damit deutlich als Erzählung. Das Abenteuer (Adventure), die Aufklärung (Resolution), die Entdeckung (Discovery) und die Bemühung (Endevour) verlagern sich hier vom Schiff in den Blick des Betrachters, der so wenig von der Südsee zu sehen bekommt wie der Leser von Forsters Reisebericht.

1773 – At the age of eighteen, Georg Forster drew his first bird. He and his father, biologist Georg Reinhold Forster, accompanied Captain James Cook on an expedition to the South Pacific. Cook was tasked to take his ships Resolution, Adventure, Discovery, and Endeavour to sea and discover the hypothetical Terra Australis – a great southern continent, that was thought to counterbalance the northern land mass. The idea of the existence of such a continent had been common reasoning in Europe since antiquity. But Cook only found small islands. After returning to Europe, Forster, based upon his notes, wrote a travelogue which quickly became a popular read and coined the European images of the strange South Seas and their inhabitants. His text also introduced the term tapu to Europe. Tapu – “the commandment to avoid”, as he defined it, is a widespread complex cultural concept in the Pacific Region. It derives from the two words ta and pu. On the island of Tahiti, the words described something “wholly marked”. Originally bearing a positive connotation, the term was reinterpreted as negative in the European usage – as it represents the mythical interdiction to touch someone, which was fought in the name of Enlightenment at the time. But, as Adorno and Horkheimer note in their “Dialectic of Enlightenment”, “the immanence of positivism, […] is nothing other than a form of universal taboo. Nothing is allowed to remain outside since the mere idea of the “outside” is the real source of fear.” Jakob Engel risks the glance to the next bus stop and confronts Forster’s narrative of the early colonial history in the South Pacific with his series of images. He dramatizes parts of Forster’s text into a form of theater script and thus clearly characterizes the travelogue as a tale. Adventure, Resolution, Discovery, and Endeavour relocate from the ship to the eye of the beholder, who gets to see as little of the South Seas as readers of Forster’s travelogue.